ooo

Infinite time, monkeys, and typewriters!

The famous story of a monkey eventually writing the complete works of Shakespeare!

You may have heard of this story, which has become more of a parody than a hope; more of a joke than a serious consideration: Given many monkeys and typewriters — as many as you can imagine — would at least one of them ever accidentally type out all the letters and words that comprise the complete works of Shakespeare?

(Note that chimpanzees are actually "apes" not monkeys. The use of the term "monkeys" here is part of the parody of the story, as this is popularly used.)

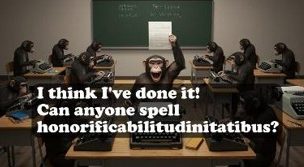

The humorous illustration depicted here, refers to the longest word in the writings of "the Bard" Shakespeare: honorificabilitudinitatibus (incidentally, this word occurs in the play Love’s Labour’s Lost, used by the character Costard the clown, Act V, Scene I — if you are a Shakespeare fan).

How many humans can write this word from memory, spell it correctly, and use it in context?

Regarding the "wow" factor in his research on the human brain, neuroscientist Andrew Huberman said, in this YouTube interview: "You just don't see in animals the elaboration of parts of the brain involved in context and planning."

Could an Ape Ever Produce

the Works of Shakespeare?

A recent study by two researchers

Two researchers based in Sydney, Australia, Stephen Woodcock and Jay Falletta, found that the time it would take for a monkey (ape) with a typewriter to accidentally replicate Shakespeare's plays, sonnets and poems would be longer than the lifespan of our universe; in fact that number many times over!

There is apparently a mere 5% chance that a single chimp could successfully type the word "bananas" in its own lifetime! And producing a random sentence — such as "I chimp, therefore I am" — is apparently one in 10 million billion billion (10^24). That's many orders of magnitude greater than the number of seconds that have elapsed since the universe began (said to be 4.35 x 10^17, or put another way: 435 000 000 000 000 000 seconds). A tall order indeed!

The primary obstacle preventing chimpanzees from achieving this complex task, is the "hard-wiring" of their brains, or more specifically, the lack of "soft-wiring." Humans possess a very significant amount of "soft-wiring," which enables us to program our brains with considerable sophistication and continuously add unlimited amounts of data to our memories. In contrast, chimpanzees have a much greater degree of "hard-wiring" than "soft-wiring." They exhibit high levels of pre-programmed instinctive behaviours and characteristics, but have only limited capacity for growth in intelligence and knowledge.

This is analogous to a computer that only has a small amount of physical memory (known as RAM), and only limited capacity to add new memory. With humans, the amount of "memory modules" that can be added has no known limit.

Additionally, the skin of apes and monkeys is considerably tougher and less flexible than that of humans — a trait evolutionists suggest we have lost. So, apologies to fans of the movie franchise Planet of the Apes, and the playful chimps in the movie series Madagascar, but chimps are not capable of producing the wide range of phonetic intonations that our mouths, throats, tongues, cheeks, and of course our brains, enable us to produce.

Also, chimps lack the opposable thumbs that humans have, as their thumbs are physically too short. This anatomical difference significantly limits their creativity compared to humans, despite the claims of some anthropologists that their evolution has granted them greater dexterity. While their hands are well-suited for climbing trees and swinging from branch to branch, they will never achieve the intricate and delicate creations that humans can accomplish!

Technical Note (not for Technophobes!)

Are Humans Closely Related to Apes?

Note that this comparison does not take account of the (serious) argumentation presented by Darwinian evolutionists who believe that apes and monkeys have arisen from a different branch of the evolutionary tree, the so-called "tree of life." However, it is often seen in the media, particularly in movies, that references are made to the "close relationship" between humans and monkeys.

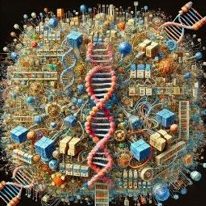

The portion of chimp DNA that matches human DNA is often cited by evolutionists, typically around 98% (with some estimates more conservative at around 96%). However, this comparison fails to account for what microbiologists, in the recent past, used to refer to as "junk DNA," that comprises about 98% of the total DNA. A study of this section of DNA has shed new light on this in recent times.

Is There Really Such a Thing as "Junk DNA"?

More information is continually emerging about the regulatory and maintenance capabilities of the so-called "junk DNA" portion, and its ability to organise and distribute cell information. This section, which is the vastly larger part of DNA, is referred to as the non-coding region. This portion comprises by far the majority of DNA (about 98%).

Yamashita, professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), said this about so-called junk DNA: “If you look at the chimpanzee genome and the human genome, the protein coding regions are, like, 98 percent, 99 percent identical. But the junk DNA part is very, very different.”

Another biologist stated that, "the myth that non-coding DNA sequences have no biological significance has been busted."

The UK's Financial Times reported on a global project into a study of "junk DNA" by a group of scientists. It stated:

"A global collaboration has discovered a vast new range of biochemical activity in the human genome. It shows that most of what scientists had dismissed as “junk DNA” is in fact a gigantic control panel with millions of switches regulating the activity of human genes."

Ewan Birney, who co-ordinated data analysis for this project, had this to say: "Our genome is simply alive with switches, millions of places that determine whether a gene is switched on or off. There are more switches than you could believe."

And Cristina Sisu, a geneticist at Brunel University, London, said, “Slowly, slowly, slowly, the terminology of ‘junk DNA’ [has] started to die.”

The term "junk DNA" is, in fact, nowadays generally dropped from the vocabulary of geneticists when describing the functionality of this section of DNA.

The "close to 98%" DNA match that evolutionists refer to, then, only applies to the 2% of DNA that contains the widely researched coding regions.

In other words, recent scientific research has proved that human DNA is actually vastly different from chimp DNA, in contrast to the claims of evolutionists.